Courtesy photo

Note: This is the final story in a series this week on the 30th anniversary of Bedford North Lawrence’s 1990 state championship.

By Justin Sokeland

WBIW.com

BEDFORD – Legends are not born, they are created. What defines a legend? Fame? Conquests? Character?

The sterilized dictionary version reads “a famous or important person who is known for doing something extremely well.” Or it could be “a person whose fame or notoriety makes him a source of exaggerated or romanticized tales and exploits.”

How about this version: “Someone who leaves behind an unforgettable impression on others. They touched lives, they’re remembered, they’re cherished.”

“Heroes,” the late Kobe Bryant said, “come and go, but legends are forever.”

Damon Bailey was already all of that. At 18 years old, he was a state icon, one of the superstars of Indiana high school basketball easily identified on a first-name-only basis. Ever since the Bob Knight visits to Shawswick, since the Sports Illustrated proclamation as the nation’s best, after four cyclone years of high school, everybody knew his name.

Only one thing was left to accomplish. And late in his final game, that grand prize was about to be ripped away. Bailey would have gladly traded all the attention, all the fame, for a state championship. That’s all that mattered. Bedford North Lawrence had finally reached the state final, and with 2:38 left in his career, the Stars were in dire jeopardy. Trailing by six points, to the top-ranked, undefeated team in the state.

158 seconds. In that time span, with 41,046 fans in the Hoosier Dome roaring in approval, Bailey cemented his place on the Mount Rushmore of Indiana basketball. The script sounds so unbelievable, likely rejected by Hollywood as too incredible for belief, yet this story begged for a perfect ending. The western hero, wearing the white hat, riding in to save the day, galloping off into the sunset.

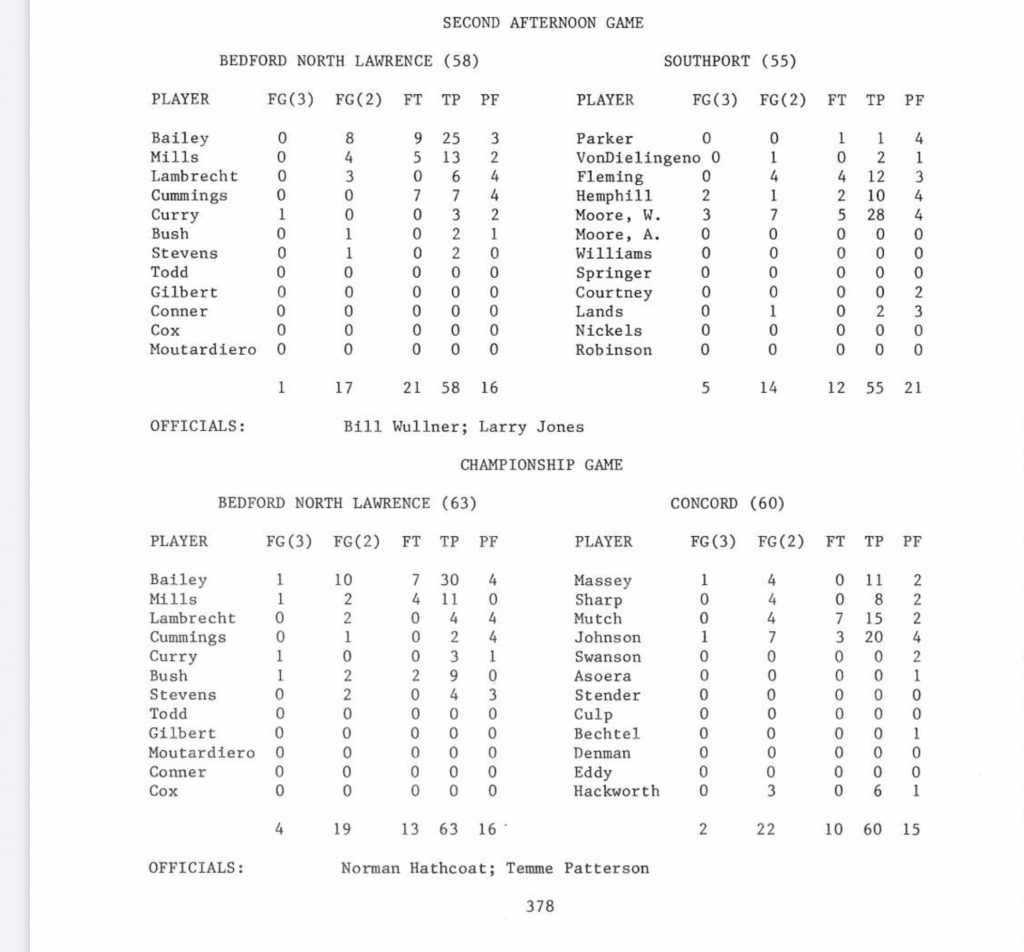

That’s exactly how those final 158 seconds unfolded. Bailey, with the Stars facing a 58-52 deficit, scored his team’s final 11 points, powering BNL to a 63-60 triumph for the ages and the school’s first state title. Fairy tales, after all, do end happily ever after.

“If you’re going to spread the season over a novel or book of any kind about Hoosier basketball,” television commentator Tom Hession said as the celebration washed over the court, “I suppose this is the way it would have turned in the end.”

Fate, divine providence, the sheer will of one of the greatest of all time, the perfect storm of circumstances – all of it converged that night.

“It was just an unbelievable ending to a time and a season,” Bailey said. “You couldn’t have written it any better. Whether it’s fate or whatever, whether we turned it up a gear, there were a lot of things that went right for us.”

How did the most famous time period in the history of Hoosier Hysteria unfold? Through the eyes of time, through the eyes of those who were on the court, let’s relive one of the greatest endings (OK, Milan’s Bobby Plump has an argument here) in championship history . . .

Courtesy photo

CONCORD 56, BNL 52, 2:38 left

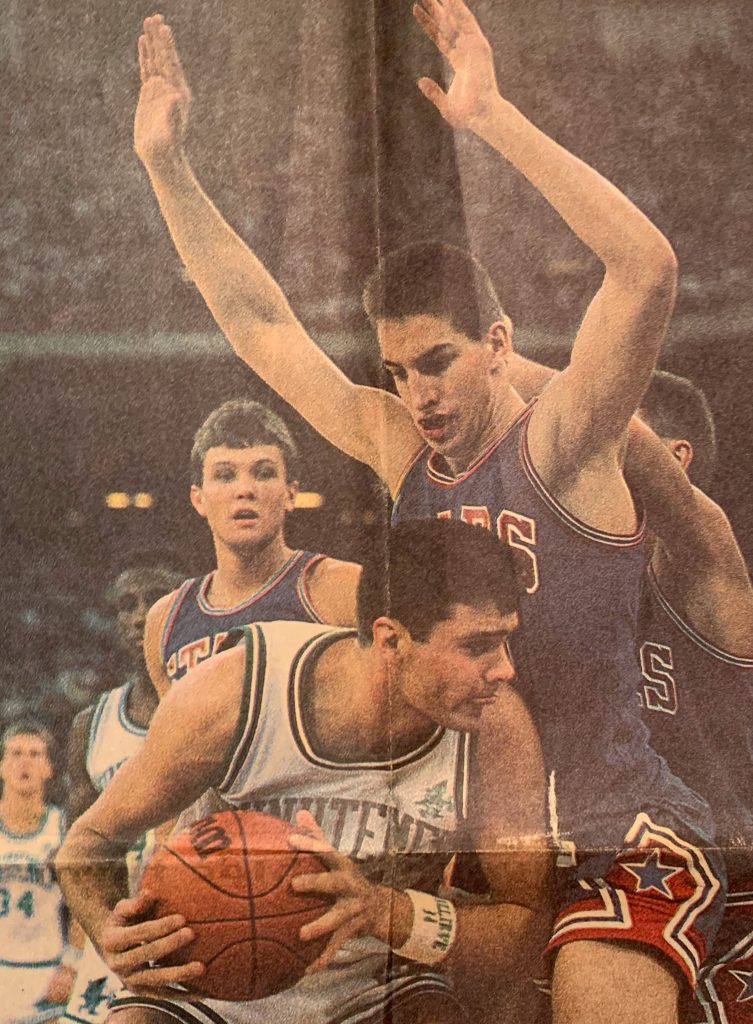

Actually, that’s skipping a lot of drama. The first 29:22 was a classic clash in itself. BNL came out hot, tearing apart Concord’s press as Dwayne Curry and Bailey hit 3-pointers, Bailey turned a steal into a left-handed layup, Alan Bush buried a trey, and Jason Lambrecht scored from point-blank range for a 24-18 advantage.

Jamar Johnson, Concord’s star and a Nebraska recruit, brought the Minutemen back in less than a minute, Bill Mutch gave Concord its first lead at 31-30, and BNL went scoreless the final 4:18 of the first half, falling back 37-32.

The Stars erased that in the first four minutes of the third, and that set the stage for tension the next 8 minutes. Tied 46-46 after three. Tied 50-50. Then Concord surged as Mutch hit two free throws, Jeff Massey popped a baseline jumper, and Johnson drew a backcourt foul on Jamie Cummings, who banged his head hard on the fall. Timeout.

Johnson, chomping on his chewing gum, came back from the break to hit two free throws. 58-52. Concord’s biggest lead of the night.

“When you’re an athlete in that situation, I never took the floor thinking we were going to lose,” Alan Bush said. “We always felt like we were going to win. Granted, it doesn’t hurt to have Damon Bailey on your team to make you think that way.

“There’s two things about that, in terms of the caliber of player Damon was and the caliber of the supporting cast the rest of us were. One, Damon never said the word ‘Give me the ball.’ We knew. It didn’t have to be said. We knew where the ball was going to go.

“We had the best player in the history of the state on our side. We weren’t stupid. I think like 9 of the 12 guys on that team were in the National Honor Society, we were an intelligent group of kids. You didn’t need to tell us.”

Courtesy photo

CONCORD 58, BNL 54, 2:31 left

After the Johnson free throws, BNL faced the press and got the ball to Bailey across 10-second line. Johnson challenged him near halfcourt, then fouled him 40 feet from the basket. Bailey converted both ends of the 1-and-1 free throws.

“I felt right then we were going to win,” BNL coach Dan Bush said, although he certainly could have tipped everyone off about that hunch during that moment. “Concord had some good players, but I think we had the best one.”

CONCORD 58, BNL 57, 1:45 left

For some reason, the Minutemen kept attacking. If the situation had been reversed, BNL would have been in “low zero” mode, running the motion offense with layup-only orders to draw fouls and salt the win away. That’s how the Stars had conquered Southport in the afternoon semifinal, scoring all of their fourth-quarter points from the line.

The Minutemen, true to the nickname, were in an inexplicable hurry. Mutch missed from 15 feet, and Lambrecht claimed the rebound. Bailey drove past one defender, avoided Johnson’s swipe at the ball, and scored while colliding with Micah Sharp in the lane. 3-point play. One-point game.

“They just kept playing the way they played, they didn’t change what they were doing,” Bailey said. “Then we make a couple of shots, things definitely fell our way, there is no doubt about it.”

CONCORD 58, BNL 57, 1:24 left

Again, Concord was content to fire, with Johnson missing a 16-footer. Lambrecht claimed that board and drew Johnson’s fourth foul in the scrum. But after a timeout, he missed the 1-and-1. Concord’s Mike Swanson grabbed that rebound and draw Bailey’s fourth foul in the fight for possession.

Swanson, a 78-percent shooter from the line, missed as well.

BNL 59, CONCORD 58, 1:09 left

Bailey snatched that rebound and dribbled into the front court, with Swanson shading him to the right. Bailey drove left, pulled up from 12 feet in the lane, shooting with Swanson’s hands in his face. That ball bounced four times on the rim before dropping softly through the net.

“There was nothing forced about it,” Alan Bush said. “It all played out smoothly. We just got it to him. There were no set plays we ran, but we knew where it needed to go. We were going to get the ball to Damon.”

“He’s Damon Bailey because of what he could do,” BNL reserve Paul Stevens said. “They weren’t going to stop him.”

“In the heat of the battle, none of us were surprised because that’s what he could do,” Chad Mills said. “Until I watched the game later, you didn’t realize how impressive it was. In the flow of the game, you were worried about a lot of things out there so you weren’t watching it, that he really took over.”

Courtesy photo

CONCORD 60, BNL 59, 0:47 left

After another timeout, Concord had to take action, and Johnson delivered, swishing a 10-footer from the baseline. It was the 9th lead change of the game.

BNL 61, CONCORD 60, 0:40 left

Bailey got the inbound pass against the Concord pressure and took off, a blue blur in the open court. As he approached the lane, Mutch stepped across and drew contact. Whistle. Concord players signaled offensive foul (Bailey’s fifth). The referee thought otherwise. Blocking foul. Bailey made both three throws.

“First of all, it was a block,” Bailey said. “I want to make that clear. I’ve watched it, watched in slow motion, it was a block.”

“Somebody is doing some pretty good scripts for this tournament, haven’t they,” Hessions asked the television audience.

BNL 63, CONCORD 60, 0:24 left

Massey rushed back, misfiring from 16 feet, and Bailey was fouled in the battle for the rebound. The Stars met for a quick huddle, then Bailey made a slow, purposeful walk to the other end for the foul shots. With the ball cocked to the right of his head, he launched. Pure. Twice. There was no way he was missing. The ultimate competitor was in his element.

“It’s just amazing,” Cummings said. “I don’t think people know how good or special he was. There were some comparisons to Romeo (Langford) or whomever, but man, he could take over a game. And he made everyone on the floor better.

“He just wasn’t going to be denied, and that’s the winner he is, not just the basketball player. That’s two different things. He beat me at everything we ever did, it didn’t matter what we did, whether it was running backward, forward, sideways, jumping, shooting, ping-ping, air hockey, golf . . . That’s just how he was made. The way he was wired, you learned that and chased that, wanted that. The whole mentality of all of us was changed.”

THE FINAL 20 SECONDS

Concord, without a timeout to plot strategy after the Bailey free throws, went for the tie. Not once. Not twice. Four times. Four shots in the longest 20 seconds in anyone’s lifetime.

Johnson from the top of the key. No, but the long rebound kicked right back to him with 14 seconds. . . .

Massey from the left wing. Nope, but that board kicked long to the opposite side where Sharp grabbed it with 11 seconds . . .

“It seemed like it was the last two minutes,” Alan Bush said. “They were shooting threes, there were long rebounds they chased down. After the first couple, you get to the point where ‘OK, one of these is going to go in eventually.’“

“They kept shooting that thing,” Dan Bush said. “Some of them were hurried, not great shots And they had pressure on them. I haven’t watched it for a while. When I do, I keep thinking they’re going to make one of those threes.

“I was asked years later ‘Why didn’t you foul?’ That gives you a chance to lose. If they hit a free throw, get an offensive rebound and hit a three, you’re beat. This way, you were still tied. I’m just glad it worked out for us that time.”

Sharp hesitated, then let it fly from the right wing. Off the rim, into the left corner where Massey beat Chad Mills to the ball with :03 remaining . . .

“For the life of us, we couldn’t grab a rebound,” Bailey said.

“Every time that shot went up and hit the rim, it was like ‘Somebody get that,’” Mills said. “The bounces just went their way. That was quite a moment, maybe relief. They had their chances, for sure. Even watching that part of the game later, they had a lot of opportunities.”

Massey’s final fling wasn’t close, and Lambrecht swooped in to grab that air ball and shovel the basketball to Cummings. Somehow, in the bedlam, the blare of the horn pierced the noise . . .

“I was glad to hear that horn,” Cummings said. “We couldn’t seem to get that ball for anything. There wasn’t a better sound than that horn.”

“Then,” Alan Bush said, “the party started.”

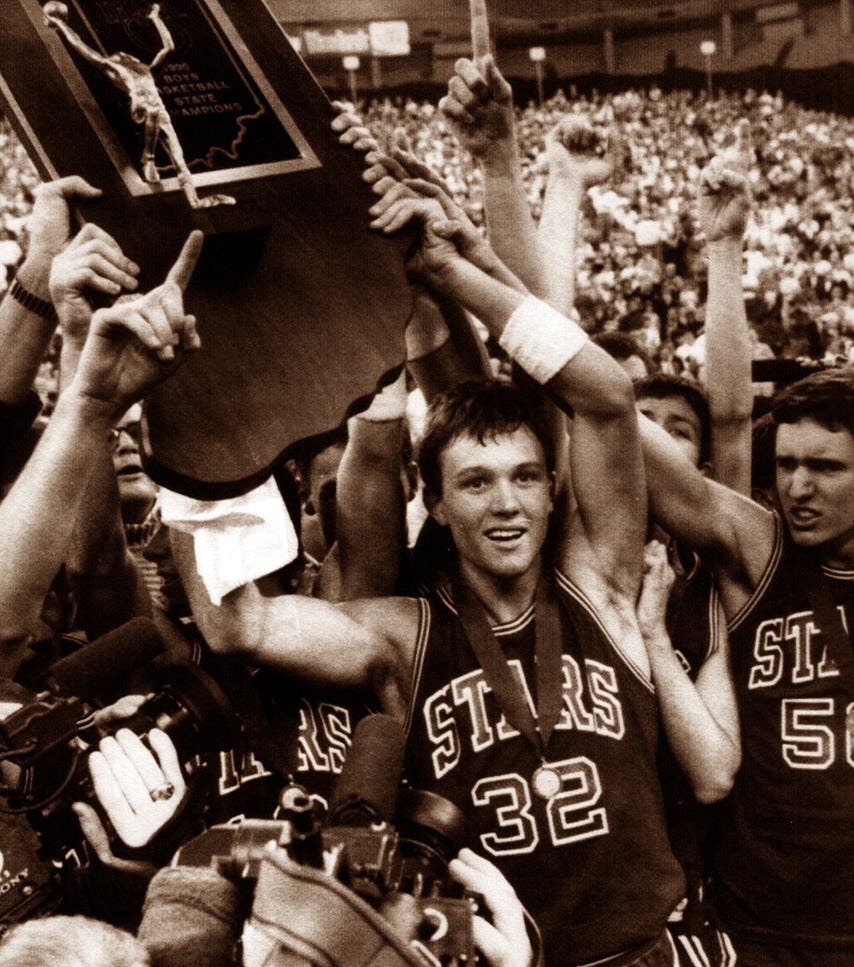

It was over. BNL had won the state championship. From that point, sheer joy, pandemonium, chaos, hugs, tears, bedlam. Beautiful.

“There’s a picture floating around of the bench right when the horn sounded,” Stevens said. “Everybody jumped up, and I’m sitting down, it looks like I’m pounding on Coach’s knee. He probably had marks on his leg where I had my claws in him. It was pretty crazy.”

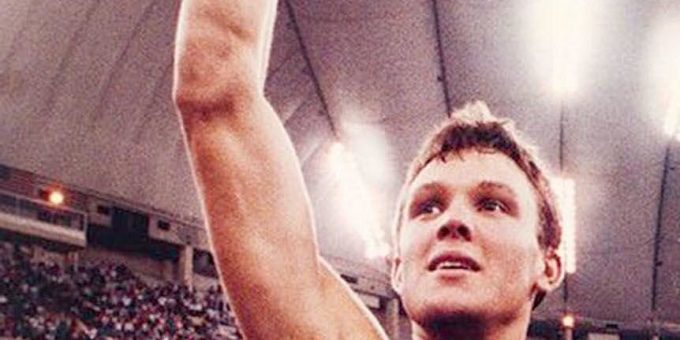

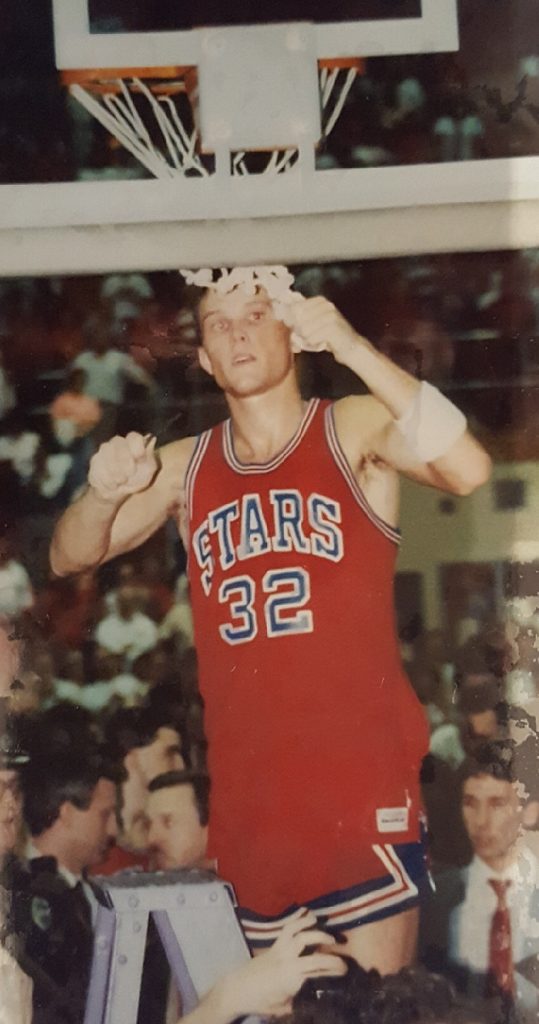

Somehow, in the midst of the team dogpile at midcourt, Bailey wrestled free from the death-grip hug of Johnny Mike Gilbert and disappeared. How in the world could the most famous player in state history escape the cameras? Then they found him. He had climbed into the teeming masses, found his parents, and was hoisted high with his fist raised in triumph. The image is everlasting.

“He’s an honest to goodness folk hero,” television announcer Jerry Baker said. And he was correct.

The celebration lasted several minutes before IHSAA officials could restore order and hand out the blue ribbons and that gorgeous, gigantic state championship trophy. Guess who held it aloft first? He had earned that.

“It was the perfect ending, for me personally, for my career, for that particular team, all that we had gone through,” Bailey said. “Dealing with everything that came along, to finally be able to lift up the championship trophy.

“There were always detractors out there ‘Yeah Bedford has a good team, they have a really good player,’ whatever they wanted to say, but once it got to playing the bigger schools and Indianapolis teams, the farm boys can’t play with those type of kids. To finally be able to climb the mountain top, for the few people we had against us, to shut up that kind of talk was definitely a driving force. I had heard it, and I knew the guys I was playing with were just as good, just as committed as other teams. To finally be able to do it was a little more special.”

Everyone celebrated in their own way. There were so many to thank. Most centered on family.

“We all found each other, celebrated together,” Alan Bush said. “When Damon sought out his parents in the crowd, a few others of us followed suit. For me, I wanted to find my mom. I knew what she had gone thought that whole year, dealing with the tension between Dad and me, the grumbling from the crowd. So I wanted to find her and my grandparents, to thank them. I got back to Dad later, thanked him for kicking my butt.”

Courtesy photo

THE EPILOGUE

Has it really been 30 years? Seems like yesterday.

So much has changed. The IHSAA kept the finals in the Dome for a while, but attendance started to dwindle. Then class basketball shifted the landscape, probably forever. Ruined it, the old-timers still say. The state finals are now held in Bankers Life Fieldhouse, and the last tournament drew about 21,000 for four games (in two sessions).

BNL’s championship, with the hero in the starring role, with the suffocating attention and interest, will never be duplicated.

The memories are alive: Dan Bush’s lucky sweater (locked under glass) was part of the Hall of Fame exhibit (washed, thankfully). Bailey’s jersey was retired. The court at BNL is named in his honor. Bush and Bailey are both members of the Hall of Fame. Bailey was named Mr. Basketball and the Naismith Award winner. Echoes.

The Stars have moved on, caught in life’s current. Jobs, families, children that have donned the BNL uniform to follow in dad’s footsteps. The championship rings (most probably don’t fit anymore, knuckles and other things have gotten bigger with age) are locked away, in jewelry boxes, in safes, the token of the toil it took to win them. If they could go back to do it all over again, they would.

“The reaction was weird,” Cummings said. “It was over, and then it’s like ‘what’s next?’ There is no next. We had done it. I felt weird the next week because we weren’t playing.

“It means a lot to me, It takes me back to the guys and the coaches that allowed me to be in that position. I wish every kid could run out on the floor and experience what we did.”

“In anything in life, you have a goal and you work,” Bailey said. “I know the time and effort I put into it, the time and effort people like Jamie and Alan put into it. You work so hard and it consumes a certain amount of your life. How do we top it? It’s almost impossible to top.”

Fans still want to talk about those days. Kids watch the YouTube video and mock the short shorts, those black shoes, the ‘80s hairstyles. Unless you were engulfed in it, it’s hard to explain. They lived through Indiana basketball history.

“It was unbelievable,” Stevens said. “Looking back on it now, and the way the game has progressed since then, it’s different, the work ethic and mentality, compared to when we went through it. When we stepped on the court, it was 100 percent, every night.

“I reflect on it. It’s something I’ll remember forever, tell my kids about. It’s hard for them to fathom. I tell kids they need to cherish things and work for everything you can get.”

“The whole 30-year thing is hard to wrap you mind around, because it does not seem like that’s remotely possible,” Alan Bush said. “Even if I make it to 90, my long-term memory will still be OK and I will remember that, the game, the caravan back to Bedford, sticking my hand out the window of the bus on the square to high-five Clarence Brown.

“Little things like that will never leave me.”

“If you devote yourself to an ideal, and if they can’t stop you, then you become something else entirely . . . a legend.” – Ra’s Al Ghul in Batman

Bedford North Lawrence, 1990 state champions. The last of the Hoosier heroes.